Has our family lost some children this way?

Family historians are frequently frustrated by children on the family tree who seem to disappear without a trace. This is understandable for earlier generations but any birth recorded since 1800 should be traceable in records of marriage, death, migration or transportation. British records since 1837 are freely available and the ten yearly censuses began in 1841.

One of the most significant social scandals of our time was inadvertently stumbled on while piecing together a standard genealogy case in the 1986 by British social worker Margaret Humphreys. She discovered a dark secret about children who were torn from their families and homeland to be sent to Australia on the promise that they were being taken from poverty to be given a better life. Many of these children were removed without their parents' knowledge or consent. Record keeping was vague. History shows that while there were some who benefited from the journey, many were condemned to a life of misery. Perhaps this happened to our missing relatives?

With the support of husband Merv, also a social worker, Margaret discovered almost 130,000 poor British children placed in community care between 1947 and 1970 were relocated to Australia without passports, social histories or even the most basic documents such as a full birth certificate. Many had been told their parents were dead. Brothers and sisters were frequently separated on the docks and sent to institutions in different parts of the country; some were loaded onto the backs of trucks (lorries) for long journeys to institutions in remote regions, controlled by people who could not have cared less for the welfare of their innocent young charges. Many felt an extreme sense of rejection by their family and country of origin or both.

Based on Margaret Humphreys' book Empty Cradles, the recently released film, Oranges and Sunshine, recounts the true story of how young British lives were irrevocably ruined in Australian with the systematic and secretive support of both the UK and Australian governments. Appropriately apologies were made by Australian Prime Minister Rudd in 2009 and UK Prime Minister Brown in 2010 but it hardly makes up for four decades' worth of wrongs committed in the past.

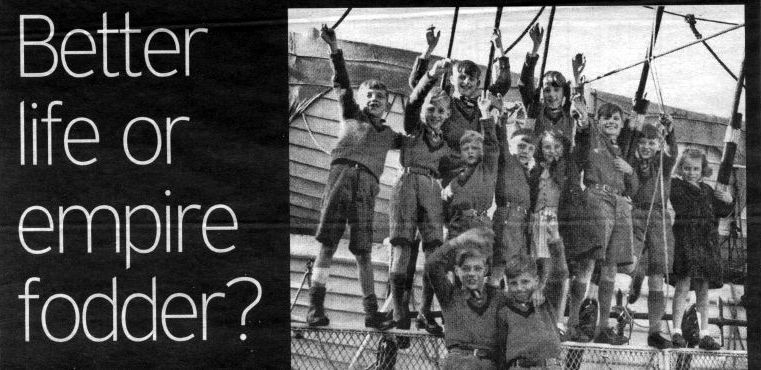

Better life or Empire fodder?

Britain is the only country in the world with a sustained history of child migration. Only Britain has used child migration as a significant part of its child care strategy over a period of four centuries rather than as a policy of last resort during times of war or civil unrest.

Child migration was inspired by a variety of motives, none of which gave first priority to the needs of the children involved. Consequently, child migrants were viewed as a convenient source of cheap labour on Canadian farms, as a means of boosting Australia's post-war population, and as a way to preserve white, managerial elite in the former Rhodesia.

The origins of the scheme go back to 1618 when a hundred "idle young people" were sent from London to Richmond, Virginia, USA. The purpose was to "clear our court from them". More would follow whenever the need arose to clear the streets and to provide child labour.

In 1620, the London Council authorised people to take street urchins to be people to take street urchins to be "bound apprentice" in Virginia. Council officers could "receive and carry these persons against their will". These children became servants or agricultural labourers.

In 1645, English parliament passed an ordinance against the practice of forced migration, but it continued regardless.

In the 1740s, about 500 Scottish children were kidnapped and sent to the colonies.

When Britain colonised Australia the practice continued, but initially child labour was provided by juvenile offenders. Between 1788 and when transportation ceased in 1868, about a quarter of the convicts sent to Australia were under 18.

Several charitable institutions formed in the mid 19th century raising money amongst middle class moralisers to transplant street urchins from the grimy, crime ridden alleys of English cities to the sunnier climes of Australia. Most were simply misguided, thinking that every child living in poverty would be better off without their destitute family around them.

The government tended to agree with self-appointed benefactors to underprivileged children. Legislation passed in the British parliament in 1850 allowed Poor Law Guardians, those appointed to administer the Poor Law Act of 1834, to fund child emigration as long as permission was sought from a surviving parent or from the child. Government migration schemes were relatively few compared to the schemes of private institutions.

An 1891 Custody of Children Act gave societies, such as Thomas Barnardo's children's homes or Father Richard Seddon's "Crusade of Rescue" authority to send destitute children to the colonies. From 1870 to the outbreak of the First World War some 80,000 children were sent to the colonies.

After the war, doubts were raised about unaccompanied minors being shipped overseas and the sometimes lax efforts to police migration schemes to prevent children being exploited or abused. The emphasis shifted to recruiting teenage boys to voluntarily migrate.

During the Depression the flow of child migrants all but stopped but after World War II the Australian government had ambitions to recruit 50,000 children a year to help build up the population during the "populate or perish" push. This target was never met because it relied on the belief that there would be thousands of displaced children and orphans after the war. Most were being cared for by relatives or in institutions reluctant to further traumatise children by sending them across the globe.

The British allowed some institutionalised children to be sent but there were soon complaints of exploitation and abuse. There had also been children sent illegally, taken from institutions without consent. By 1967 the schemes had all but ended. The final party arrived in Australia in 1970. It is estimated that child migration programmes were responsible for the removal of over 130,000 children from the United Kingdom to Canada, New Zealand, Zimbabwe (formerly Rhodesia) and Australia.

Humphreys began an investigation into the migration schemes in 1987 and her findings, that many children had been deported despite having living parents, shocked many. She established the Child Migrants Trust to provide counselling and to try to reunite wrongly deported children with their families. Sadly, many have returned to the UK to learn their parents have recently passed away.

If you or a Blencowe family member were caught up in this practice, we'd like to hear from you. If you suspect that you have a misplaced relative contact the Child Migrants Trust.