Blencowe Brides

1. Elizabeth Secole

Having come late to the Blencowe line and the Blencowe Family Association, there was little, if anything, to do in the way of original genealogical research once I had established the link between my C19th Thomas Blencowe in Souldern and the Brackley Blencowes. I therefore started to look at Blencowe Brides. I have only just embarked on this and my researches are still at the “armchair philosopher” stage – based on books and the internet only, but Anne has asked me to share what I have so far, starting with Elizabeth Secole. Please do share any additional or conflicting information that you have with me.

Elizabeth came from Eynsham in Oxfordshire, when she married John Blencowe, being his second wife, in the mid 1500s. I hypothesised that, as she had married the heir to the manor of Marston St Lawrence, she was unlikely to be short of a bob or two. Her father was apparently John Secole of Stanton Harcourt.

A Family of Wool Merchants

I was able to find evidence of a family of wool merchants called Secole1 in Eynsham, and the two adjacent villages, namely Stanton Harcourt and South Leigh (a chapelry of the former). Unfortunately the parish records do not start until too late for our purposes. The family appears to have originated in Stanton Harcourt rather than nearby Eynsham – certainly there are earlier records extant for the former than the latter.

This was an area with a high sheep population in medieval times, with lots of uncultivated heath for rough grazing, until the enclosures of the eighteenth century.

Despite the vicissitudes of the previous century:

- the recurrences of the Black Death or the Plague in the 1470s and 1480s

- the murrain killed off the Lord of the Manor's entire flock save for one ewe and her lamb in 1453 – which cannot have left the Secole family's flock unaffected

- the uncertainties of the Wars of the Roses which ended with the Battle of Bosworth in 1785 and its dreadful effect on national trade

During the late 15th century and the 16th century, the Secoles in Stanton Harcourt had amassed fortunes out of wool. Of course with Henry VII on the throne, a canny administrator, who quickly established economic stability in the country, the time was ripe for traders to prosper.

The Secoles appear to have spread their wings to Eynsham in the early sixteenth century – it had a market and two annual fairs, since the 1130s. The town was also at the junction of several trade routes, including a ferry point across the Thames. Too, since the Plague, there had been vacant shops, and presumably therefore property was cheaper than hitherto. It was well situated for an up and coming family of wool merchants to extend and consolidate their trading influence.

William Seacole (d. 1527)2, a wool buyer, owned 120 sheepi, and in approx 1525 was taxed on goods worth £16, the second highest assessment in the parishii. A William Seacole (d. 1569), also a sheep owner, paid the highest contributions c. 1543 and 1547, and left freehold lands in Northmoor and in Stanton Harcourtiii. Sheep were probably important at South Leigh, as at Stanton Harcourt, throughout the Middle Ages. In the 1540s John Seacole (Elizabeth's father?) described in 1546 as a woolmaniv, was twice taxed on £40 worth of goods in South Leighv, and in 1552 left a flock of 100 ewes there and lands in Oxfordshire, Gloucestershire, and Wiltshire.

Their trading links went at least as far as the capital. There are surviving records referring to a debt action in the Court of Chancery, Six Clerks Office, between 1515 -1518 brought by William Secole of Stanton Harcourt against William Bryteyn, merchant. From the mid to late sixteenth century onwards Secoles appear to be being married and baptised in London, so clearly a trading presence was established. There are records of a Richard Secole3, a wool trader too, across the county border into Gloucestershire, at Dydmorton (modern Didmarton), probably an offshoot of the Oxfordshire family.

The Secoles acquired substantial lands in Stanton Harcourt, Eynsham and the surrounding villages as well as their wool trade activities. In 1517 the Secoles of South Leigh had acquired Perch closes in Tilgarsley, in Eynsham, which a William Seacole sold in 1595 together with buildings4 in Thames Street Eynshamvi. Lands in Eynsham are also referred to in their wills. In 1505 William Seacole (d. 1527) of Stanton Harcourt purchased an estate in Old Woodstock. William's son Robert5 gave the Woodstock estate in 1535 to his own brother William, who sold it in 1564. They may also have had lands in Milton: there is a record in the Star Chamber of 1558 of a John Secoll proceeding against Richard Stokes, Robert Harewood and Michael Ashfeild (sic) for the destruction of a hayrick.

It is possibly this amassing of landed property by her family that made Elizabeth Secole an acceptable marriage partner to John Blencowe of Marston St Lawrence. John's first wife, Agnes Pargiter, had been from the same social milieu, i.e. the landed gentry, as the Blencowes, although her family also had extensive sheep and wool interests. The Secoles on the other hand were yeoman and tenants, albeit of increasing stature in the Eynsham/Stanton Harcourt area. Unlike in the late eighteenth and nineteenth century, there was no entrenched snobbery about “marrying trade” as long as there was wealth, as many younger sons of the gentry were set up in trade if neither the law nor the church appealed. However a respectable alliance in terms of matching wealth would be required, for the eldest son in particular.

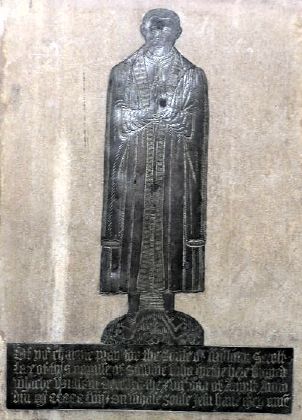

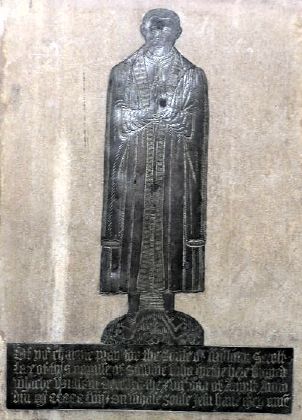

The Secoles of Elizabeth's times were able to afford substantial monuments. A brass on the south wall of the nave at South Leigh depicts William Seacole of South Leigh (d. 1557); in the 17th century it was in the north aisle and included Seacole's four sons and three daughters. Lost monuments include a marble to Robert Seacole (d. 1512)6 and his wife Alice.

This transcription and the photograph it contains, are Copyright © St. James the Great South Leigh Parochial Church Council, 2006. Reproduction is permitted with this acknowledgement for research and non-profit purposes.

|

Flat wall mounted brass figure with inscription panel beneath.

Of yor charyte pray for the Soule of WILLIAM SECOLL

late of this parrishe of Sothlye who lyethe here buryed

which William [departeth] the xvii day of August Anno

Dm' mccccclvii on whose Soule Jesu have m'cy ame'

The book “A History of Oxfordshire” mentions William Seacole and gives a date of 1557.

|

|

In the 15th century an earlier Robert Secole was of sufficient standing and reputation that he was appointed as a trustee for the Manor of Stanton Harcourt on the death of Sir Robert Harcourt (1470), and for John Harcourt (1475). He is mentioned in the surviving records of Chancery pleadings to the Archbishop of Canterbury as Lord Chancellor – the existence of the disputes suggesting that the appointment of someone outside the family was a wise move, as so often is the case in the 21st Century also.

Family disputes existed within the Secole family too. The National Archive holds Chancery Pleadings:

- 1556 -8 Thomas LAWRENCE v. James ORME, late the husband of Anne, formerly the wife of John Secole: Messuage and land in Kingham, demised by John Secole, gentleman, to complainant and the said Anne for the benefit of her children by her first marriage: OXFORD

- 1553-1555 William SECOLL v. Robert MARTEN his son-in-law. Detention of deeds relating to lands in Eynsham: OXFORD.

I have used later pleadings to good effect to establish links on other lines, and intend to look at these – one day, when finances permit, and my palaeographical skills have improved!

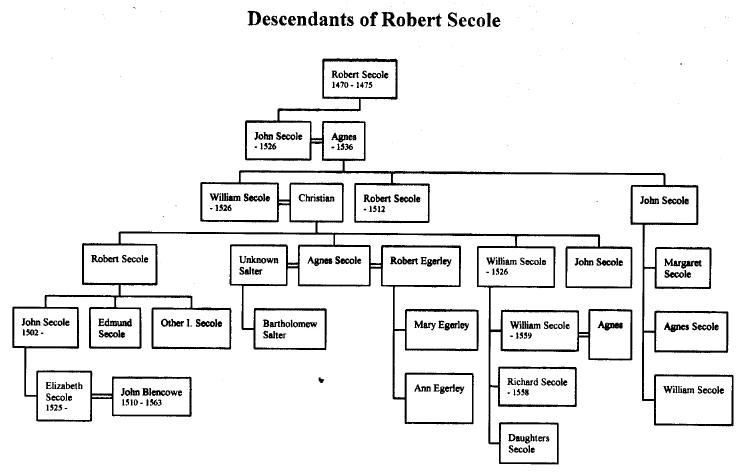

Neither the IGI nor Rootsweb appeared to offer much real evidence of the Secole family relationships. The recycling of a narrow pool of names within the same family group does not, of course, help. I turned to some wills downloadable from A2A, which did clarify the overall family grouping and give some coherence to a family tree but alas did not enable me to slot Elizabeth into a precise position. My palaeographic skills for this era leave a lot to be desired, and I will be happy to share my copies – particularly with anyone who is willing to assist in a full transcription. I have been able to extract names and relationships however so that a family tree can be reliably drawn up.

|

|

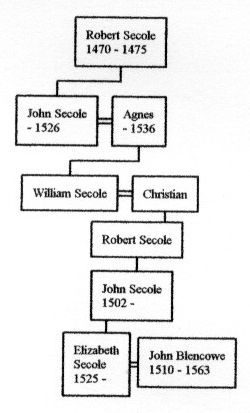

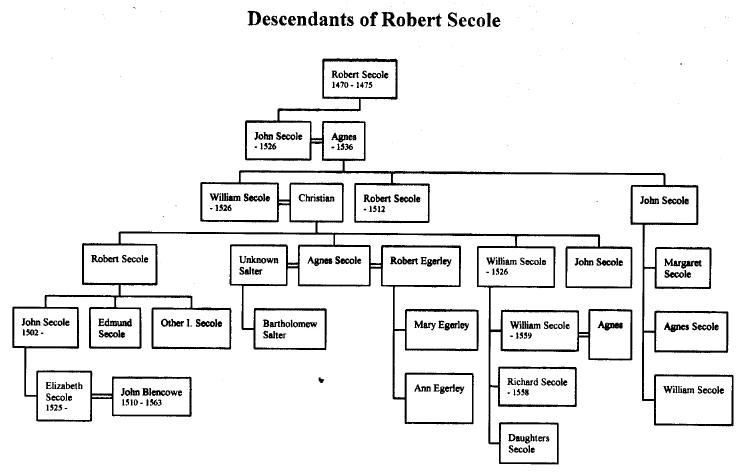

Probable ancestry of Elizabeth Secole

wife of John Blencowe Esquire

|

They were clearly a very godly lot and left substantial sums to the local churches. Robert Seacole's Will dated 12/5/1512 is concerned before any other consideration with bequeathing “my Soule to Almighty God and his mother Seynt Mary and to all the Seynts in heaven” followed by numerous bequests to the church and provision for the costs of casting a bell in his memory. Robert seems to have died a widower as there is no mention of provision for Alice7, and without issue and with only one godchild – these facts suggest a younger man to whom death was coming untimely. The will gives the impression of having been written in haste The will refers to his brothers William and Robert (is this the scribe's error, while writing in some haste, with death imminent – should this have been Richard, or was he referring to William's son? Or should this be brother John referred to later in the Will?). His remaining bequests are to his brothers, and to nieces and nephews. The following family members are specifically mentioned:

- brother William Secolle

- brother Robert Secole, but this is likely to be an error

- John Secole & Robert Secolle brother of John

- Agnes Secoll the daughter of William Secoll

- John Secole sonne of Robert Secolle

- Brother William Secolle [again] & brother's sonn John Secole

- Margaret & Agnes brother John Secoll's daughters

- William Secolle son to John Secolle

- Robert Secolle brother to John Secole

His brother, William's death was not until some fourteen years later, having made his will on 15 November 1526, by which time William's sons and daughters are grown and there is a crop of young grandchildren to be remembered in the will. Elizabeth Secole would have been as yet unborn, or a tiny child. Either way, the will does not mention her. William's Will, which seems an altogether more carefully constructed document, in addition to providing first for the proper disposition of his soul, leaves sums for prayers for the souls of his father and mother John and Agnes and for his brother Robert. William's will therefore ties together 4 generations of the family. I feel that we can hypothesise a fifth – namely that John's father was the Robert Harcourt relied upon as trustee by the Harcourt family of Stanton Harcourt.

William, after making some small bequests to his godchildren, of whom two are named, but it is clear there are a number, turns to his family. He bequeaths first to his wyfe [Christian, I think – frustratingly, this name is difficult to read!] £100 of “ready money” and the use of his “householde stuffe” for her lifetime and providing further “I will she disposes of it at her own pleasure”, thereby ensuring that she would be treated with respect for the remainder of her life as this bequest could effectively have left his heir with a large empty property to furnish, at considerable expense.

The following family members receive bequests:

- John Secoll the sonn of my sonn Robert: £10 to be held by his father until he be married – if he dyes before to his brothers and sisters (who receive £5 themselves on the same terms) that lyve after him

- Daughters of my sonne William: £5 (on the same terms as above)

- William sonn of my sonn William: £10 (on the same terms as above)

- Bartholomew [Salter?] the sonne of my daughter Agnes to be held by executors until of lawful age: £5 (?)

- Mary and Ann Egerley daughters of my daughter Agnes and [name erased] Egerley her sonne £5 (until they be married etc)

- Master Robert Egerley and to his wyfe, daughter Agnes various chattels

- Robert my sonne land and appurtenances in Old Woodstock

- William my sonne — house in Eynesham

- Robert my sonne — difficult to decipher what he was left, but my best guess at the moment is a tenanted property

- Grandson John, sonne of Robert

- Grandson Edmund, sonne of Robert

There are other bequests to non-family members and gifts of chattels to family members including his 'beste brasse potte' to his daughter Agnes.

The next will is that of William Secole of South Leigh — interestingly the same will dated both 27/4/1557 and 6/4/1560 has been separately proved — the latter in London with a Probate Inventory (possibly of trade goods?) which clearly will have to be investigated further. Have duly bequeathing his soul, money to repair the church; a gift to the poor8 and to his various godchildren, William leaves the following to family members:

- Sons William and Robert -£100 each

- Sons John & Richard £100 each given by my father's will (not yet located)

- Johanne and Agnes my daughters 100 (marks?)

- Agnes my wyfe £100, my free land in Eynsham for life (which he provided was to go thereafter to his eldest son [i.e. John] and his heirs male by seniority); my estate of Moddings (?) until my son William attains 21years but to Robert and his heirs if William has no lawful heirs; a lease bequeathed to Agnes

- Land in the Lordshippe of [unreadable] to John my eldest sonne

- The remainder of the estate to John and in default to his wife and their unnamed daughters and their heirs

He appoints Agnes and their sons to be the executors.

The last will is that of Richard Secoll of Dydmorton, Gloucestershire dated 27 September 1558. The family relationships do seem to fit in with the Oxfordshire Secoles. After taking care of his soul, bequests to the church and to the poor, to his godchildren and others, some of who are clearly in his employ, he leaves

- £200 to his well beloved wife (Amy?)

- in essence the rest of his estate is divided between his two daughters Agnes and Chrisell (Grisell) but in default of their surviving then to his brother's son Richard Seacoll

- his uncle Robert Seacoll and his brother William Seacoll are both mentioned

I have still not established Elizabeth's precise placing in this extended family, but I think we can be fairly certain that we have the right grouping. Possibly the answer lies within the chancery pleadings of Lawrence v Orme.

The Tudor period was one of considerable social mobility, and the Secoles were clearly becoming prosperous merchants, capitalising on the favourable economy that followed the end of the War of the Roses, their wares much in demand for the many hangings carpets and tapestries which typified Elizabeth interior decoration, and the innovation of the stocking knitting frame which brought cotton and wool stockings within reach of the populace at large. Elizabeth's marriage to John Blencowe would have been another step upwards for this family of prosperous wool traders. We can speculate that Elizabeth caught John's eye while he was transacting business with her father and uncles, with the added benefit of forging closer links with trading partners and presumably an acceptable dowry. Despite the fashion for poets and minstrels writing and singing of romantic love, I suspect our ancestors were pragmatic in such matters.

© Ruth Jenkins, 2007

Footnotes

- The name seems to be spelt variously: Secole, Secoll(e), Seacole being the most frequent variations.

- His will is analysed below: possibly Elizabeth's grandfather

- His will is also analysed below and the family relationships that he describes do fit into the Eynsham and South Leigh family group, but they are common for the time

- These may or may not be the same as Glover's tenements of which the record of his purchase still survives.

- Robert inherited the estate from his father

- His will is analysed below

- mentioned as his wife in the memorial in South Leigh church

- Was this because of increasing wealth in the family or the fact that the Abbey had been dissolved by now, and no longer there to give alms and support to the indigent?

The following are the source document references given in The Victoria County History: Vol 12 Oxfordshire (1990), which I was my main source of information outside the Wills.

- Woodstock Boro. Mun., B 83.

- ibid. E179/ 161/175

- ibid. E 179/162/235, 253; O.R.O., MS. Wills Oxon. 185, f. 6; Bodl. MS. d.d Harcourt c 50.

- L. & P. Hen. VIII, xxi (2), p. 99

- P.R.O., E 179/162/235, 253.

- Cat. Anct. D. vi, C 7874; C.C.C. Mun., Twyne transcripts, ii, p. 542; Chambers, Eynsham, 83.

C.C.C. Mun., Twyne transcripts, ii, pp. 424-54, 482-6,488; Cal. Close, 1476-85, p. 389. C

C.C.C. Mun., Twyne transcripts, ii, pp. 502, 542.

updated: 3 December 2007