A Notable Blencowe

Robert Blincoe (1792-1860): a Tale with a Twist

From workhouse orphan to indentured child-slave during the industrial revolution, Robert Blincoe's political, personal and turbulent story became the centre of a social revolution in Britain.

So who was this knock-kneed little fellow who became the poster boy for one of the great reform movements of the age, of any age?

Robert Blincoe was born in 1792 into a world in the chaos of rapid industrialization. By 1796, aged four he was he was abandoned to the St Pancras workhouse in London. It was a miserable place to be, but at least he was well fed. The workhouse children were the unwanted children, often illegitimate, but sometimes left there due to parental poverty and they were indeed the lowest of the low. These children, who began their generally very brief lives in those misnamed places of charity - workhouses - run by the local parishes all over England, were used as factory fodder.

The fate or identity of Robert Blincoe's parents remains unknown. Robert thought his parents, on one side at least, were genteel and that for some of his early years he was loved. This belief shaped his remarkable character and Robert always had a sense of himself as a human being and worthy of being treated as such. He never identified with his cruel masters and he never saw himself as a victim.

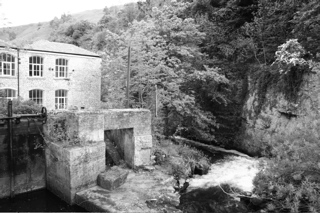

At seven, Robert, with a cart full of his fellow workhouse children, was sold as an "Apprentice" terms of engagement 14 years to the Cotton Mill owner at Lowdham, 200 miles north of St Pancras where he worked 14 hours a day, 6 days a week. When that Mill closed he was sent to Litton Mill where the treatment was the same.

After fourteen years of agony, Blincoe rebelled. He fought back against the mill owners, earning beatings but gaining self respect. He joined the campaign to protect children from ruthless profit-seekers and gave evidence to a Royal Commission into factory conditions.

After suffering years of unrelenting abuse: it was this iron belief that saw him survive the workhouse, then the satanic mills, and a chequered early life in his own cotton-spinning business. He married, Martha Simpson in 1819. In 1828, a fire in his spinning machinery destroyed his business leaving him destitute and imprisoned in Lancaster Castle for bad debts. Robert became a cotton-waste dealer working with extraordinary tenacity to earn enough money to educate and keep his own children from the factories. His son, Robert graduated from Cambridge - unimaginable for an unlettered child of the workhouse.

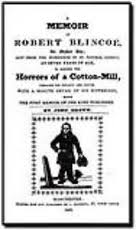

In 1832 the journalist, John Brown, recorded Roberts biography in the pamphlet, A Memoir of Robert Blincoe, An Orphan Boy and gave it to social activist, Richard Carlile who, in 1828, published the tale in his newspaper, The Lion, in five weekly episodes. The 100 page biography exposed the poor conditions in cotton mills resulting in a government investigation into the cotton mills.

Oliver Twist was Charles Dickens' second novel, serialised in 1837, just five years after Blincoe's tale was published as a pamphlet. Dickens, as a parliamentary reporter, would have followed intimately the raging debates about working hours and conditions when Blincoe's testimony, to committees and in his memoir, was repeatedly drawn upon.

Roberts's story is of being tortured, suffocated by cotton fibres and ultimately crippled by the need to bend for hours below fast moving cotton spinning machines to clean them out as they continued to run. So why was this story so different that it likely caught Dickens' imagination?

Robert became a militant leader and a successful businessman as time progressed, in fact a very wealthy one albeit illiterate. This leads us to a ghosted memoir that he was helped to write by a journalist John Brown and a cause that was taken up by a Manchester union leader John Doherty. The cause: the elimination of child and worker slavery (initially a modest demand for a 10 hour work day). Robert joined Doherty in this cause and made it famous nationwide. Its likely this injustice and the fame of the published memoir caused Charles Dickens to conceive of the central character Oliver an orphan in a world morally defunct in the treatment of poor children.

Undoubtedly the opening chapters of Oliver Twist owe something to Blincoe's life but a more direct introspective account of Blincoe's life came from Frances Trollope's 1840 novel, The Life and Adventures of Michael Armstrong, the Factory Boy.

Trollope actually met the publisher of Blincoe's memoir, and her novel, although unlit by any of the genius of Dickens, was relished by reformists and a sensation at the time.

The well-meaning Trollope lifted entire tracts of Blincoe's life, rarely stopping to alter words. She sensibly included the scandalous scene when the malnourished mill child crept out at night and stole food from the mill owner's better-fed pigs. With such fact, why would any novelist send out for imagination? Rich and dense, this calls for detailed reading.

Robert Blincoe's life stands on its own as an engrossing story that dramatically illuminates an age and a society. Contributors to this article: Julian Blincoe, Douglas Bain and Roger Blinko

References: A review of John Walker's book, The Real Oliver Twist: A life that illuminates an Age in the Sydney Morning Herald 30 /01/2006

Review in The Guardian, 28/09/2005 entitled Grandad? Is that You by Nicholas Blincoe http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2005/sep/28/fiction.shopping

Here Robert Blincoe describes the cruelty of the overseers.

"Robert Woodward, who had escorted the apprentices from Lowdham Mill, was considered the worst of those illiterate vulgar tyrants. If he made a kick at Blincoe, so great was his strength, it commonly lifted him off the floor. If he struck him, even a flat-handed blow, it floored him; if, with a stick, it not only bruised him, but cut his flesh. It was not enough to use his feet or his hands, but a stick, a bobby or a rope's-end. He and others used to throw rollers one after another, at the poor boy, aiming at his head, which, of course, was uncovered while at work, and nothing delighted the savages more, than to see Blincoe stagger, and to see the blood gushing out in a stream!

So far were such results from deterring the monsters, that long before one wound had healed, similar acts of cruelty produced others, so that, on many occasions, his head was excoriated and bruised to a degree, that rendered him offensive to himself and others, and so intolerably painful, as to deprive him of rest at night, however weary he might be. In consequence of such wounds, his head was over-run by vermin. Being reduced to this deplorable state, some brute of a quack doctor used to apply a pitch cap, or plaister to his head. After it had been on a given time, and when its adhesion was supposed to be complete, the terrible doctor used to lay forcibly hold of one corner and tear the whole scalp from off his head at once. This was the common remedy; I should not exaggerate the agonies it occasioned, were I to affirm, that it must be equal to anything inflicted by the American savages, on helpless prisoners, with their scalping knives and tomahawks."

Taken from A Memoir of Robert Blincoe by J. Brown. 1828.

A film clip worth viewing

Julian Blincoe was involved with the BBC in a news item for BBC East Midlands Today. The result of a day spent filming in Notts, Derbyshire and Cheshire is a clip about two minutes long relating to his gt,gt,gt grandfather Robert Blincoe. The BBC posted it on the web.

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-derbyshire-15667646