Two distinguished Soldiers: Lawrence Cave Blencowe and Oswald Charles Blencowe

The First World War has effectively passed out of living memory and the Lost Generation who fought it has all gone. However interest in it is greater than ever, and on the 100th anniversary of the Armistice I thought it might be appropriate to look at two distinguished Blencowe brothers who were killed in action. We can consider what we might learn about them, about the War they fought in and what lessons we might learn today.

Revd Charles Blencowe was the last member of the family to own Marston House. His eldest son Arthur was a regular soldier, who commanded a battalion of the Lancashire Fusiliers. The second son William served with the Canadian forces and was badly gassed, while the two younger sons are the subject of my research. There were also two daughters: Marjorie who was a nurse in the War and Cecilia.

Oswald Charles Blencowe 1890 - 1916

2Lt Oswald Charles Blencowe 6th Battalion, The Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry

Oswald Charles Blencowe the youngest son was born in 1890. He attended the Dragon School in Oxford where coincidently my brother now teaches. Oswald joined up at the start of the War as part of Kipling's Army. While most continental countries had systems of conscription, Britain had a relatively small regular army.

With the benefit of hindsight that Army should not have been committed (and largely destroyed) at the start of the War but should have been used for training and cadre force on which to base the mass army that would be needed. However, this was not the way of it and the loss of many of Britain's pre-war trained regulars meant that battalions had to be raised from scratch from enthusiastic amateurs like Oswald.

Oswald initially served in the ranks in a Public Schools Battalion of the Royal Fusiliers, before being awarded a commission in the 6th Battalion of the Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light infantry. Again, such a battalion would have been composed almost entirely of inexperienced volunteers, with only a handful of pre-war regular officers and NCOs. The battalion arrived in France in July 1915. Oswald seems to have thrived in this environment as shown in this letter from a brother officer.

“In the line he was of immense value to us, and in the most trying hours, when things were as bad as shells and foul weather could make them, he showed that rare kind of cheerfulness which does not offend nor depress by its artificiality. He set a high value on music and poetry. He sang well, and was strongly heard in a dug-out – carols, songs and choruses, old English songs, and Gilbert and Sullivan. One day he pulled out the books he always carried with him – Omar Khayyam, and two volumes of the hundred best poems and three of us lay awake reading aloud to one another.”

The First Battle of the Somme is chiefly remembered for the disastrous outcome on the first day.

However, what is less well remembered is that the Battle went on for another three months. During this time the British Army learnt from its mistakes, developed new tactics and fought with increased effectiveness until the battle petered out inconclusively in November 1916. Oswald’s battalion was at the front of this steep learning curve.

The last major offensive was the battle of Le Transloy which lasted from the 1-18 October 1916. On the 7 October 1916 Oswald was temporarily attached to the 12th Battalion of the Rifle Brigade, a unit that had lost many of its officers. The Battalion was part of an attack by 60th Brigade east of Guedecourt. They were using more sophisticated artillery techniques notably the creeping barrage. Soldiers would advance behind a moving barrage of artillery which would only lift off the enemy trenches a minute or so before the attacking troops got there. The assaulting troops would encounter little resistance and would clear the dugouts with grenades. At the same time, stopper barrages supressed German machine gun and artillery position up to a kilometre behind.

If this was not done they would bring fire down on prepared beaten zones in front of the enemy trenches making it impossible to advance. The trick lies in the timing and the maths and they didn't always get it right. It appears that the barrage lifted too soon before Oswald’s company reached their objective, Rainbow Trench. This allowed the Germans time to recover and fire on the attackers.

The initial attack failed and all but one of the company officers in the two lead companies were killed including Oswald. The trench was taken by the second wave later in the afternoon. News of his death reached his parents six days later. Oswald was buried close to where he fell on 13th October 1916. However, Oswald's grave was subsequently lost and he is commemorated on the memorial to the missing at Thiepval.

He was hit by a shell in the head in front of his men about ten yards from the enemy’s line, but such details are needless and unsatisfying; we know what he was when alive and in what manner and with what spirit he must have died. The circumstantial details are useless trappings.”

Lawrence Cave Blencowe 1887 - 1917

2Lt Lawrence Cave Blencowe. C Coy 2/10 the Liverpool Scottish Regiment

Lawrence was Oswald's older brother and like Oswald an Oxford Blue. He was also a distinguished sportsman - a trait that has persisted in many Blencowes to the present day (although not the writer). A rugby forward he captained the Yorkshire county XV and played for the North of England against the South Africans in 1915.

Lawrence was married at the start of the war and may have delayed his enlistment for that reason. However, he joined up in 1915 and initially served as a private and later a sergeant in the West Yorkshire Regiment. He was then commissioned in the King's Liverpool Regiment. The 10th Battalion of the King's Liverpool were a territorial battalion before the war and were better known as the Liverpool Scottish. With Scottish antecedents and traditions they considered themselves a cut above the rough Scousers of the rest of the regiment.

Two Battalions of the Liverpool Scottish were raised; the 1/10 and the 2/10. 1/10 was better known counting among their officers Captain Noel Chavasse RAMC one of only three men to add a bar to their VC. The 2/10 arrived in France in Feb 1917 and was no doubt anxious to emulate the fame of the 1/10. Among Lawrence’s brother officers was the actor Basil Rathbone.

Trench raiding was a common feature of the Western Front. The objectives were varied: to find out information, kill the enemy, destroy enemy weapons, and take prisoners or to encourage fighting spirit. These were usually carried out at night by small groups of ten men or so. Rifles were rarely carried, as clubs, knives, revolvers and grenades were handier. Firearms were carried but only used in an emergency or just before leaving. The trick was get into position, stay silent for as long as possible, achieve the objective and return to the trenches before the Germans had a chance to react. However, as previously mentioned the British Army was continually innovating and decided to experiment with larger scale trench raids in company strength during daylight. The aim was to take and hold a section of enemy trench for a longer period.

Lawrence Blencowe with his strapping build, leadership qualities and aggressive sporting record was ideal for this sort of work.

'Dicky's Dash' was a company-sized daylight trench raid named after Captain Alan Dickinson MC and carried out by C Company 2/10 the Liverpool Scottish - probably about 100 men. It took place just south of Bois Grenier on the afternoon of 29th June 1917. It met with determined resistance from the enemy and although successful in gaining a foothold in the German line, took heavy casualties both in the enemy trenches and on the return to the British frontline. Lawrence never returned from the raid and it is unclear exactly what happened to him.

Lawrence was commanding a bombing party and he was last seen climbing over the top of the trench. The Company lost two officers and fourteen other ranks killed and over half the raiders were killed, wounded or missing. Germans losses were higher and their section of trench severely damaged. The raid was judged to be a success, although the experimental daylight raids were later abandoned. The 2/10 had a short life; it was merged with the 1/10 in early 1918 as both battalions had suffered heavy casualties.

Lawrence's body was never found although a surviving letter from his parents to the War Office enquired whether he might have been taken prisoner. It was not to be and Lawrence is commemorated on the memorial to the missing at Ploegsteert. He left wife, Dorothy and two young sons, Oswald and Lawrence.

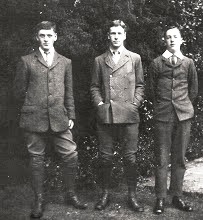

Brothers William, Lawrence and Oswald in happier times in 1905

The Marston branch of our family suffered grievously as a result of the Great War. Two sons were dead and another permanently broken in health. The two daughters and Arthur never married and although Lawrence left two young sons they left no descendants. Rev. Charles's younger brother, Alfred was more fortunate – none of his nine children perished in the war, although four served with distinction. His descendants, of whom I am one, are numerous. A very cruel lottery indeed and we can only think what might have been.

It is worth thinking why they died.

The forces of nationalism, demagoguery and bigotry propelled those two fine young men (and millions like them) to an early death.

Even more depressingly those forces re-emerged twenty years later and had to be dealt with again. In my teaching I often ask the pupils to think what my grandfather, a veteran of WW1, must have felt when he saw the boys he taught sent off to do it all again.

The world seems a darker place than it was and the forces that led to the tragedies of the last century appear to be on the march again. It would be appropriate to remember Lawrence and Oswald and think about the world they would have wanted.

They were lovely and pleasant in their lives and in death they were not divided.

Charlie Blencowe,

Sutton, England